Encouraged by Elizabeth Reid’s talk at the ‘How the Personal Became Political’ symposium at ANU, I decided to take a look into her significant archive at the National Library of Australia. I want to use this blog post to look at some very interesting material I discovered, particularly the documents, letters and speeches Reid and other produced during International Women’s Year, 1975, and the year’s signature event, a huge UN conference on the theme of ‘Equality, Development and Peace’ in Mexico City. Here, the intersections, and perhaps contradictions, of a government-mandated feminism are apparent.

Reid was appointed, after a lengthy application and interview process, to be Gough Whitlam’s advisor on women’s affairs in 1973: the first person to ever occupy such a position.[1] Designed to advise the prime minister on how to “remove or at least reduce all legal, social, educational and economic discrimination against women”, Reid’s appointment intersected with Whitlam’s broader ambition of capturing the spirit of (what he at least imagined as) Australia’s 1940s human rights activism.[2] His administration signed on to or ratified dozens of United Nations treaties and covenants, catching up on two decades of international law either bypassed or procrastinated over by his conservative predecessors.

Whitlam wanted, as he put it in a cabinet submission around the celebration of International Women’s Year, for “Australia to become once again a pacesetter for the rest of the world in advancing human rights”, a re-conceptualising of Australia’s international position seen as a break with pro-American policies and contributing to the reposition of Australia as an independent middle power.[3] Yet Whitlam’s idea of human rights, was in many ways out of keeping with that of the burgeoning women’s movement that Reid and Australia’s International Women’s Year committee represented.

A “looking-glass equality”, which allowed women access to male professions and roles, would perpetuate what the Committee labelled “sexism” – unequal divisions of labour in the home that perpetuated the social construct of male and female, public and private spheres.[4] As feminist Shirley Castley put it, in a document prepared for the Australian contingent to the Mexico City conference, which lasted from the 19th of June to 2nd of July 1975:

Equality is not the answer so long as our society remains sexist. Equality would mean women becoming more like men. What is needed is for people to become more like human beings.[5]

The United Nations had declared 1975 to be International Women’s Year three years earlier, yet anyone who thought that this conference would focus on the plight of the world’s women were to be disappointed. The powers that were in the UN, most centrally the group of third world nations around the G-77 and their plans for a New International Economic Order (NIEO), had reached a peak of influence. Articulated in 1974’s Charter of the Economic Rights and Duties of States, the NIEO pointed to the need for a for a more equitable distribution of the world’s wealth, particularly through increases in aid, the democratisation of global financial institutions and removing unfair tariff barriers protecting the industries of developed nations. As Roland Burke argues, 1968’s International Conference on Human Rights in Tehran had seen the meaning of human rights almost entirely subordinated to the economic needs of the nation state.[6] Mexican president Ojeda Paullada, a particularly vocal defender of this project, wanted to ensure that:

the Conference of the International Women’s Year does not become a forum for enumerating the political and social problems that women face in contemporary society; on the contrary, the meeting must approve a series of international documents of fundamental political value which are defined in accordance with the principle of international responsibility.[7]

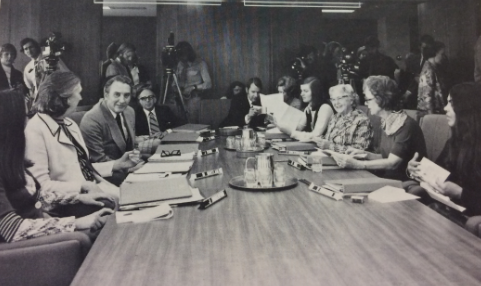

Australia’s delegation, made up of ten feminists “who had been working on Australian government programs specifically related to women” as well as four career diplomats, received a confidential briefing to this effect. Based on experienced at a preparatory conference held in March in New York, delegates were warned that third world nations would try “to link the advancement of women with struggles against colonialism, imperialism and racism with economic development and [the] need for a greater sharing of the world’s resources”. Against this reading of women’s struggles as subservient to the post-colonial state, the Australian delegates were instructed to argue for “fundamental human rights” and “general solutions to the problems and injustices facing women irrespective of particular political and economic circumstances”.[8]

Here, the agenda of second wave feminism met that of Australian foreign policy. The group of women’s activists were advised to “promote Australia’s concerns and interests”, in particular through demonstrating “a sympathetic and cooperative concern…for the developing countries”, which was part of Whitlam’s broader strategy of presenting Australian foreign policy as “an independent one”. Yet, whilst expressing sympathy with those nations at “different levels of development”, the delegation was to focus on “unifying objectives and themes” rather than “extraneous political and economic issues”, such as dealing with issues of underdevelopment that impacted women in the third world.

While viewing “moves to change the present structure of international economic relationships as justified and deserving support”, “continuing reservations” persisted.[9] As Jim Cairns put it at 1974’s meeting of the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), such fundamental changes to the economy needed to wait for a “recovery in world economic conditions resulting from the pursuit of sound policies of economic management”. It isn’t hard to catch Cairns’ drift – developed nations took precedence in matters of global economics.[10]

As such, a careful rhetorical balance was necessary. Reid’s statements to both the March preparatory meeting in New York, and to the conference’s plenary session in Mexico adopted the third world’s language of decolonisation to push a western feminist agenda. At the preparatory meeting, presided over by the sister of Iran’s Shah, Reid protested that “women are the oldest colonial and underdeveloped people in the world”.[11] Reid attempted to carve out a place for western feminism in this highly-developmentalist conference through the theorising of the term ‘sexism’. “We must cease being afraid to use these words”, Reid instructed, for like “racism, racial discrimination…and the taking of territories by force”, sexism was a form of “power over other human beings”. “Patriarchy”, Reid insisted, “was just another form of colonising people”.[12]

Both the Conference’s key planks of “equality” and “development”, proposed and widely supported by the developing world, needed revising. “Equality is a limited and possibly harmful goal”, Reid argued at one of the Mexico conference’s plenary sessions, as it would lead to a “strengthening of the status quo”. At the conference’s preparatory gathering, she had argued that equality merely extended the limited rights and privileges men enjoyed to women – locking them into “an already inadequate and destructive structure.” This critique of equality was tied to a critique of the third world’s position on development. While allowing that demands for a more equitable global order were “far from peripheral” to women, levelling the playing field between developed and developing worlds would only force developing nations into the drudgery of the western way of work – “larger institutions, distant workplaces, inflexible hours, a dehumanised environment which suppressed the social, cultural and spiritual life of its workers”.[13]

Thus, “[t]he transferring of the Western economic growth model to other countries no longer seems desirable”, and this was especially true for women, Reid argued, as “capital intensive development, unemployment and underemployment hit women hardest”. As such, any notion of a new international order must place women at the centre, for history showed that after a systemic revolution or transformation “the new society benefits women no more than the old”. For if women are treated merely as abstract equals within the development process, rather than peoples subordinated by complex social and cultural practices, the myths and prejudices that keep women in their place will continue to hold say.

Reid and her fellow Australians did not succeed in having a more universal understanding of women’s rights adopted by the conference, which instead endorsed a pre-prepared statement and action plan which spoke in clearly gendered terms of the women’s place as separate but equal partners in the development process. Yet, they had successfully presented to an alien forum the case of second wave feminism, which happily dovetailed in this instance at least with Australian government policy. While cautiously endorsing fundamental global economic restructuring, Australia’s participants in the conference critiqued the meaning of decolonisation via a language of anti-sexism. Equally, this case shows how the meaning of human rights was up for debate in local and global settings. Was human rights merely the extension of legalised equality to those previously excluded – women and colonial nations – or the undermining of more subtle social attitudes and expectations that perpetuate discrimination? Was it, as Shirley Castley put it, about women becoming more like men, or everyone becoming more human?

[1] Michelle Arrow, “Working Inside the System: Elizabeth Reid, the Whitlam Government, and the Women’s Movement”, Vida: Blog of the Australian Women’s History Network, accessed 13 March 2017, available at: http://www.auswhn.org.au/blog/elizabeth-reid/

[2] E. G. Whitlam. “FOR CABINENT – International Women’s Year 1975”. Elizabeth Reid Papers, MS 9262, Box 32, Folder 13, National Library of Australia.(NLA).

[3] Ibid.

[4] “International Women’s Year: Report of the Australian National Advisory Committee,” Parliamentary Paper No. 201/1976 (Canberra, Government Printer of Australia, 1976).

[5] Shirley Castley, “Sexism – introductory remarks”, in Women in Australian Society: Analyses and Situations (Canberra: Australian National Advisory Committee for International Women’s Year, 1975), 8.

[6] Roland Burke, “From Individual Rights to National Development: The First UN International Conference on Human Rights, Tehran, 1968”, Journal of World History 19, No. 3 (Sep., 2008), pp. 275-296

[7] Ojeda Paullada’s speech to the Consultative Committee for International Women’s Year, March 1975, quoted in Roland Burke “Competing for the Last Utopia?: The NIEO, Human Rights, and the World Conference for the International Women’s Year, Mexico City, June 1975” Humanity 6, No. 1, Spring 2015, p 50.

[8] “CONFIDENTIAL: International Women’s Year – Background”, Elizabeth Reid Papers, MS 9262, Box 43, Folder 87, NLA.

[9] “Overall Approach of the Austalian Delegation”, in World Conference of the International Women’s Year – Mexico City, 19 June to 2 July 1975 – Brief (Canberra: Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 1975), 8.

[10] STATEMENT BY THE TREASURER, THE HON. DR. J.F. CAIRNS, M.P. TO THE MINISTERIAL MEETING OF THE OECD PARIS 28 MAY 1975, available at: http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query=Id%3A%22media%2Fpressrel%2FHPR08001812%22

[11] Inward Cablegram, 10 March 1975, Elizabeth Reid Papers, MS 9262, Box 42, Folder 84, NLA.

[12] “Statement by the leader of the Australian delegation – Ms Elizabeth Reid”, 21 June 1975, Elizabeth Reid Papers, MS 9263, Box 42, Folder 84, NLA, p. 3, 8-9.

[13] Ibid, p. 6.

One thought on ““Women are the oldest colonial group in the world”: Human Rights, Women’s Rights and Third Worldism in Mexico City, 1975”